Twice a year, White Sands Missile Range opens up one of the most impactful sites in 20th Century history, and twice a year thousands of vets, history buffs, homeschoolers and gawking tourists drive hours into the middle of Nowhere, New Mexico, to walk a desolate stretch of scrub desert and remember.

"Important" doesn't begin to cover it.

I'd first heard of Trinity Site when I started my obsessive research about things to do in El Paso. I'm not much of a WW2 buff, but I am married to a man who is. When I got an alert that the site would be open the first weekend in April, I threw the family and some sunscreen in the van and headed out.

It's a roughly 2 and a half hour drive up and around the northern reaches of White Sands Missile Range, which is still an active testing range for other ammunitions. The road winds through some of the most godforsaken parts of New Mexico. Despite the emptiness of the area, traffic picked up the closer we got to the site. At the turnoff to the northern gate we unexpectedly ran into protestors. Apparently the local towns were never designated as a risk zone and compensated for the exposures that many of them believe led to increased rates of cancer in their community. It was a surprising and sobering introduction.

After 45 minutes waiting to get through the gate and a quick check of the van, we were allowed to proceed on strict orders not to stop and not to take any pictures except at Trinity Site itself. We crossed our hearts and then started on the last segment of our journey, twenty minutes of flat asphalt twisting deeper into the nothing of the desert. We kept an eye out for the Arabian Oryx that infest the entire range but didn't see any.

Finally we pulled up to Trinity Site, which is carefully fenced and policed with multiple guard towers. A sea of RVs and smaller vehicles filled the parking lot. People milled around taking pictures. Burgers were being grilled and sold 100 feet from Jumbo, a massive 25 foot, 214 ton steel jug originally intended to hold the bomb during the test. A small trailer sold commemorative shirts as a fundraiser for the military unit on the other side of the entrance. The far corner of the parking lot was walled off by a forest of port-a-potties.

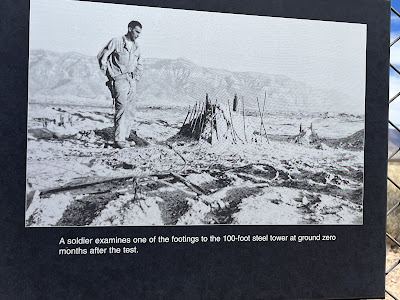

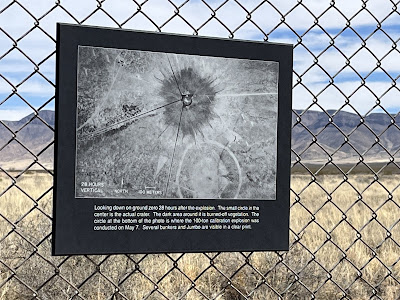

The actual detonation site is a short walk down a dirt road bordered by tall chain-link fence. Scattered piles of poop offer proof that the unseen Oryx do exist. A small booth offered information, reassurance about the fairly safe radioactivity of the area, and a chance to use a Geiger counter and a vial of depleted uranium. A sign warned that removing any Trinitite, the glass made by the explosion, was a federal crime. If you pay attention, you can see that you're walking in the crater, several feet lower than the rest of the area. All that remains of the tower that held the bomb is a single footing, a waist-high monolith of rusted steel and concrete, next to a squat and sober obelisk that marks the exact impact point. The fence is lined with photographs and newspaper clippings documenting the process of building the bomb, the site, the aftermath. Bits of grey-green Trinitite glint underfoot.

What I found most jarring was the replica of Fatman, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. It's barely 10 feet long, a chubby steel blimp that seems too impossibly small to have wrought such mind-numbing, war-ending destruction. It is so hard to believe that something so unimpressive killed 40,000 people outright, searing shadows into concrete, with up to 80,000 more dying over the following weeks and years. Horrifying doesn't begin to cover it. And this was so insignificantly small compared to the nuclear bombs in our arsenals today. Sometimes perspective is chilling, not illuminating.Oh well.

We had the opportunity to take a bus out to MacDonald Ranch, where the plutonium core of the bomb was assembled and where the scientists worked prior to the test. However, between the heat and the crowd we decided to pass. We drove the long, twisting road back off post, past the protestors and on to Highway 380. Instead of driving home the way we'd come, we took a right and made a giant loop.

We wound up driving through the Valley of Fires. About 5,000 years ago a local peak erupted and left a lava flow that is up to 160 feet thick and covers 125 square miles. The highway runs right through it; ridges and folds of black rock curl all along the road. It's frankly amazing. If I have a spare weekend before the summer starts scorching, I might make another trip back up there to do the Malpais Nature Trail. As it was, with two hours and one more stop to go, we took a quick pic, geeked out, and drove on.

Since Rick had never been to White Sands National Park, we stopped in to show him the dunes. For the curious, it sits in the middle of White Sands Missile Range off Highway 70. I recommend following the signs and not confusing the two--your welcomes at each will be very different. Even though this was my and the girls' third or fourth visit, it was still fascinating. The gypsum sand is cool to the touch, and very fine. The girls chucked their shoes and barreled barefoot up the dunes, rolling down and promptly covering themselves in clinging sand. Rick took a more measured approach but took a little bushwhack over a couple dunes and met us back at the van. I took the opportunity to snap a couple of Bren's senior photos and then herded everyone back into the van for the trip home.