A few months ago, Rick and one of

our friends conspired to surprise me with a kid-free weekend. We boxed up the children and shipped them off

with Wonder Woman—who has six kids of her own—for three days of camping. Instead of heading down to Anchorage or going

to do something romantic and couple-y, we elected to drive into the wild North and

out of cell service before anyone could change their minds about the

arrangement.

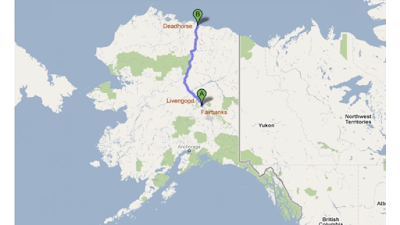

Thirteen hours from Fairbanks to Deadhorse. Six hours from Fairbanks to Anchorage. This state is enormous.

The Dalton Highway is one of the

most remote roads in the world. Running

from Livengood to Deadhorse and Prudhoe Bay, it was built as a truckers’

road and parallels the Alaska Pipeline. It’s thirteen or so hours of

remote wilderness where people can and do die.

It’s been on my Alaska bucket list for years. Researching it, though, I wasn’t sure what to

expect—internet advice was pretty evenly split between “it’s not a big deal,

just don’t be stupid” and “don’t ever do it because your car will break and

bears will eat your face.” I planned for disaster. We aired up Rick’s spare, packed some extra

water, bugspray, shovel, propane heater, and my good jack in his truck, grabbed

my battered (I prefer “well-loved”) Milepost and headed up the highway.

The first two hours of the trip

we were on the Elliot, a tangle of a highway from Fairbanks to Livengood. We saw our first moose mom about the same

time we left the cell-service area.

Honestly, this was the worst part of the road; pitted asphalt is worse

than packed dirt.

The Dalton doesn’t look like it

wants to hurt you. It’s a pretty

unassuming two-lane dirt road when you get on it. (Less than half of the Dalton is paved.) Of course we stopped for a picture at the

sign, taken by a couple of very friendly guys on their own wild-hare road-trip. We would continue to play tag

with these guys up and down the highway.

After the sign, the next big

marker is the Yukon River. This famous

river runs across the state, originating in the Yukon Territory in Canada and

then draining into the Bering Sea almost 2,000 miles later. It is about half a mile across, and you cross

it on a bridge that is about as much wood as it is metal. The river is impressive, and almost as

impressive is the bridge itself. It can

flex up to 2 ½ feet to accommodate for temperatures, and the pylons were built

by creating water-tight tunnels 25-30 feet below the surface for the workers to

work in.

The bridge that crosses the Yukon. I did not expect it to be made of wood, but it went well with the dirt highway on either side of the river.

A floating camp on the Yukon. Kind of awesome.

The Door Dog.

Looks legit and not terrifying at all. This is actually not too unusual for rural Alaskan architecture where the emphasis is more on cold and bear proofing and not aesthetics.

A pair of velociravens on the pipeline. For scale, that pipeline is 4 feet in diameter and about 16 feet off the ground. The birds are freaking huge.

At the river we stopped at the

unimaginatively named Yukon River Camp on the advice of a local friend who used

to drive buses up to Prudhoe Bay. She

recommended the burgers, and they did not disappoint. We got to pet the friendly door-dog and read

the story of the infamous Yukon River Camp Bear, who apparently set up shop in

the restaurant one winter and had to be forcibly evicted.

After lunch we headed over on a

whim to the small cabin run by the Park Service, where we got the skinny on the

Dalton by a wonderful, chatty ranger named Sheila. She gave us up to date road conditions,

recommendations about where to stay and which colorful locals to talk to, and

annotated the pamphlet she gave us. She

was a little surprised when I asked her to sign it as well.

We weren’t sure how far we were

planning to go; we were just kind of driving on a whim. As I had mentioned earlier, the road was

still an unknown entity. There are some

gut-clenching turns and drops with colorfully descriptive and appropriate names

given by the truckers such as “Rollercoaster” and “Oh Shit Corner”—the first is

a long, steep drop followed immediately by a long, steep climb, and the latter

is a sharp double-blind curve on a hill.

All told, though, the road was much better than I expected. It’s rutted

and bumpy, with a couple of car-swallowing potholes, but completely

drivable. Even the trucks, the dangerous

18-wheeler Gods of the North Road, were not a problem. We pulled to the side whenever we saw one

coming in either direction and they graciously slowed as they passed. As a result of this arrangement, no rocks

were flung and no windshields were chipped.

Our next stop was the Arctic

Circle. This was our original

destination because of the sign, but we had been warned by friends not to

expect too much. They were right. I was

whelmed. It is literally just a sign,

partially covered in stickers, that marks the boundary of the Arctic Circle. It’s a popular tourist stop for those

tourists that make it this far north (only about 1% of people who come to

Alaska). Other than that, its only other

appeal is the outhouse. Of course we

stood in line so I could get a picture because that's what you do when you go to the Arctic Circle.

Then we got back in the truck and headed North again, officially in the

Arctic.

There is some truly beautiful

country up here. Hillsides fuschia with

fireweed, teal rivers braiding through the valleys, and vistas for miles. You are acutely aware of how big the world

is—and how small you are.

The pipeline is a constant companion.

We stopped in Coldfoot for

gas. This was another less-than-whelming

place, but still satisfying to my quirky soul.

The whole town is built on a single road that loops off the

highway. It is just a place for truckers

and campers to get some sleep, some gas, and some expensive food. The gas wasn’t cheap, either, so if you ever find

yourself up this way I suggest bringing your own. The tiny post office made me smile, though,

especially with its sign.

Because Alaskans.

Next we stopped in Wiseman, a

small non-town that looks more like a survivalists’ senior center, which apparently

throws a big 4th of July celebration every year. The hill-people join the citizens of Wiseman

and the occasional nosy tourist for a day of barbecue and jug music. We had been explicitly told to talk to Clutch, 8-Ball,

and Jack. Rick and I thought it would be

awesome, especially since it was the 4th, so we took the three mile

detour to explore. We were welcomed to

Wiseman with a sign for the Wiseman Cemetery…and, directly underneath, a box of

assorted pans and shoes marked “FREE.” I wish I’d gotten a picture.

The bridge inspired confidence.

We were a day early for the

celebrations. Tents were still being set

up and grills wheeled to the grassy commons, but it just felt a little awkward

and entitled to roll up and be all “Hi, nice to meet you, now feed us.” We

decided to keep driving instead.

Naturally, we ran into someone who had also driven the road that weekend

and did stop by on the right day, and had a fabulous time eating and carousing

with the citizens. Maybe we’ll try again

next year.

After Wiseman, there was nothing

but road, sky, and the occasional roadside outhouse. It was gorgeous. I didn’t expect it, but the rest of the road

was actually in pretty good condition, both dirt and asphalt. It was the smoothest part of the trip.

We passed the last spruce tree and made the change from the taiga (the northern boreal forest that circles the Arctic) to the tundra (the treeless lichen-fields that stretch to the Arctic Ocean). We drove through Atigun Pass, which passes through the Brooks Range and is

the highest road in Alaska. It was less daunting than I had expected, with the

added bonus of seeing an ermine. Ermine

are adorable little murder machines.

They are little weasels about 8 inches long, brown and white in the

summer and white with black tips in the winter.

Our little fellow bounced across the road, head and tail sticking

straight up, carrying a vole almost as big as he was and looking immensely

satisfied with himself.

Once we were through Atigun Pass,

the road leveled out and the mountains started to give way to tundra, the flat

expanse of lichen and moss that runs all the way to the Arctic Ocean. At this point we had been in the car for 9

hours, with 4 more to go until Deadhorse.

Now, there isn’t much in Deadhorse except for oil rigs and truckers, and

you can’t even get to the ocean without expensive tour tickets bought 24 hours

in advance. Therefore we made the

decision to stop at Galbraith Lake, which Sheila had recommended to us.

These look like some variant of fireweed, but I called them the Stranger Things flowers.

Don't be fooled by the rocks. This moss and lichen depresses about three inches underfoot and springs back up behind you. It's like walking on a mattress.

Even the plants need coats up here.

A couple miles down the turnoff

we passed a primitive airstrip and found the campgrounds, marked solely by a

rutted road, a block outhouse, and a faded informational sign about the lake

and the two parks, Gates of the Arctic and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge,

that flanked the highway. A small river

rushed down to a lake that reflected the sky and the far-away mountains. We picked a spot to set up our tent and

prepped for battle.

I’m only half joking when I say

that.

I’ve mentioned before that the

mosquitos are sometimes referred to as the state bird of Alaska. I’ve lived all over this country and I will

say this: There are mosquitos, and then there are Alaskan mosquitos…and then

there are Arctic mosquitos. This last

group lives in a desolate place where food only comes through seasonally or

against good advice. Ergo, the first

whiff of sweat and carbon dioxide and they materialize out of the ether, ready

to suck the unfortunate animals into jerky. We

drenched ourselves in DEET and set up the tent as quickly as possible, and then

sprayed that down, too. It kept the bugs

off, but only just. By the time we

dragged the sleeping bags over the bugs were testing their luck on the

tent. Luckily (for me), Rick tastes

better than I do, so he got the lion’s share of the mosquito cloud.

We ate dinner in the truck, a

package of surprisingly tasty rehydrated chicken alfredo. After all of my excessive packing, I’d

forgotten spoons. Rick saved the day

with a utensil he MacGuyvered out of a can with his knife. We cleaned up and then wandered for a bit,

taking a ton of pictures.

The river wasn’t very big but could be heard everywhere. It looked so pristine, I was tempted to take

a drink. I ultimately decided against

it. While ancient humans would drink

from rivers and lakes all the time, they also, as Rick so eloquently puts it, “spent a lot

of time at the sh*tting log.” Battling Giardia or any other critter-gifted

intestinal parasite or bacteria is not anywhere on my bucket list.

Anyway, the night was great. The tundra is pretty comfy because of all the

lichen. Even though I woke up with every

rustle of the tent, the night passed uneventfully, with neither bear nor

caribou nor murder-weasel to disturb us.

The next day it was drizzly and

wet. As we headed back towards the

highway, we saw a pair of rain-dark caribou.

It’s always cool to see animals, and they proved to be just the

beginning. When we came down from Atigun

Pass we saw a muskox! They are usually

on the tundra, so the fact that we saw one south of the pass was pretty lucky. We also saw a silver fox, another moose mom

and her calf, multiple blotchy snowshoe hares, velociravens, a trucker who actually waved back,

and ground squirrels. The last were

pretty neat because they were living in a hole in the asphalt, the clever

little beasts.

The drive home was much the same

as the drive up except for one last gift from the highway. Read anything about the Dalton and you’ll

read about flat tires. We had made it

hundreds of miles with no issues, neither chip nor flat nor busted axle, and

then about fifty miles from the Dalton/Elliot junction, a tire popped.

What can I say? Alaska’s a giver.

Rick fixed the flat while I

documented our quintessential Dalton experience and humbly reminded him that I

had been the one to make sure we had a complete jack and the spare was aired

up.

Some people don’t like driving

just to go somewhere; they want a purpose, a destination at the end of the

road. Hours of mountains and rutted

roads and millions of trees indistinguishable from each other sounds boring to

them. It’s never just the destination

though, is it? I spent two days with my

best friend, making stupid jokes and mapping out the future and just being

together in one of the wildest parts of our world. Boring?

I’d do it again in a heartbeat.