A couple months ago, one of our friends invited us to help butcher a moose. We felt pretty special to get to participate--I mean, how often to you get to help break down a moose? Offered a share of the meat in return for our labor, we packed up some knives, grabbed a cooler, threw the kids in the bus and headed over.

Everybody knows a hunter, and a lot of people have butchered chicken or fish or rabbits or even a deer or pig, but a moose is in its own category. For starters, a bull moose can stand up to 7 feet at the shoulder, weigh 1500 pounds, and have an antler spread of 5 feet. In North America, only the bison and the occasional polar bear are bigger. The critter we helped with wasn't 1500 pounds, but it became clear pretty soon after we arrived that there was plenty much moosen to go around.

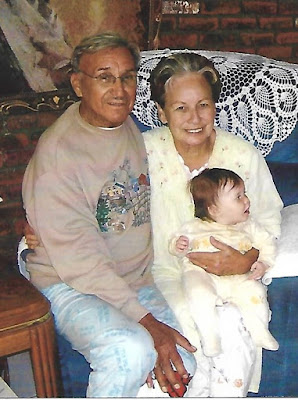

*Rick wants a reminder that this is only one leg of this animal. In addition to three other legs, there were also two bags of torso meat--making this Rick-size haunch only 1/6 of the meat that was processed that night.

As the sun set, we and seven other families--kids included--fell to work. That sounds like a lot of people to cut up a single critter, but remember--this wasn't some scrubby Arizona white-tail. The moose was quartered and hung from a beam. Four men cut the meat from the bones; the kids carried it to a nearby table, where some of the women cut off connective tissue, picked off leaves and hair, and cut it into more manageable portions. From there it was carried, platter by platter (and tub by tub in some circumstances) to the house, where it was rinsed as necessary and further processed into either roasts, steaks, or ground into burger.

Because we're a little dark--and, frankly, because this was a golden opportunity--I and the other homeschool moms gave an impromptu anatomy lesson, pointing out muscle fibers, veins, and the difference between ligaments and tendons. We also discussed responsible hunting practices, wildlife management, the life cycle, and the transfer of energy from producers to consumers. Since several of the adults were also medical providers, trauma was discussed. The older kids (who could mostly be trusted not to cut their fingers off) helped cut meat. For the most part, the kids bore their forced education well.

I found the bullet. In a thousand pounds of meat, it's the equivalent of getting the wishbone.

I don't love hunting. I don't love blood. I don't love butchering animals or feeling meat-scum cake under my nails or the monotony of parceling and packaging meat--I don't even particularly love moose meat--and yet, in this circumstance, it was...fun. Fulfilling. Satisfying. It was as if it appeased a deep, primal memory of a tribe coming together after a hunt, working together to ensure their survival. Like that was how life was supposed to be. Everyone had something to do. Older children watched babies so parents could skin and carve and process meat, younger children filled and carried and emptied trays. Nobody complained or slacked off. People joked and laughed the entire time. It was incredible to feel so strongly like we belonged, to be so in sync with our friends and neighbors and even a couple complete strangers. It felt, for a few brief hours, like we were with our tribe--and it was amazing.

Moose still isn't my favorite, and I still don't love blood-crud under my nails, but I would do this again in a heartbeat. I never imagined that this would be part of our Alaskan experience.

I'm so glad it was.